By Tim Banninger

The study of ancient lithic (stone) technology provides us with invaluable information about our ancient past. We must not forget that regardless of the time period, there are human traits that remain constant throughout time. It is nothing short of human nature which ensures that every advantage is utilized to it’s fullest and it is necessity which inspires our greatest technological advancements. Life in the Paleolithic period presented man with challenges unlike any

man has faced in the modern era. To cohabitate with the species that existed on earth then would likely be beyond anything conjured by even the wildest of imaginations.

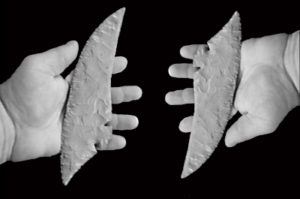

Assessing ancient stone tools finds modern man at a disadvantage simply because of modern tool concepts, production, and the resulting perception. Our perception of tools is based on form and function while functionality and ergonomics of application are all that is required. Tools assist man in performing the daily tasks at hand but those tasks are relative to the period and the associated way of life. What we refer to as extreme wilderness survival provides us with only a scant notion of everyday life in the Paleolithic world. If we refer to a Paleolithic stone cutting tool as a knife we induce the misconception of a modern technology and it’s usage. However, by breaking down the concept of cutting into multiple functionalities we can achieve a better understanding. Incising, scoring, ripping, and slitting are just a few of the underlying concepts that may better explain the daily tasks performed as well as the stone implements which assisted in these endeavors. A biface projectile point can be easily assessed from just a photograph but properly assessing ancient flake tools out of hand would be nearly impossible even for those with extensive familiarity. A lack of conchoidal fracture without the support of further context behind the discovery of a tool will most certainly result in the assessment of “natural occurrence” by most archaeologists in North America as few have enough experience to know the difference.

In the latter half of the 19th century, the word eolith was added to the English language. At the time this was a categorization for stones which displayed possible signs of having been created by man but sufficient data was not available to assess them as man-made tools. Instead of investing more time into further study of these anomalies they have, for the most part, been written off as natural occurrences. This is despite the lack of sufficient data to support the idea that natural forces are responsible, therefore the skeptical argument remains purely speculative in my opinion. Evidence from the Cerutti Mastodon Site in San Diego suggests man was present in North America as early as 130,000 BP. If this is truly the case, the current archaeological record is certainly lacking as a means of supporting this theory. Unfortunately, with at least 42 archaeological sites providing evidence of Pre-Clovis occupation in North America, remnants of the Clovis first model can still be found in the craws of many archaeologists. A comparison between artifacts collected from these Pre-Clovis sites with those documented by Charles C. Abbott in the late 19th and an early 20th century reveals some amazing correlations. Prior to the 1930’s discovery near Clovis New Mexico by a paleontologist, it was believed that man’s earliest presence in North America was approximately 10,000 BP as theorized by Ales Hrdlicka, whom many of us consider as a blight to the history of North American archaeology.

In the latter half of the 19th century, the word eolith was added to the English language. At the time this was a categorization for stones which displayed possible signs of having been created by man but sufficient data was not available to assess them as man-made tools. Instead of investing more time into further study of these anomalies they have, for the most part, been written off as natural occurrences. This is despite the lack of sufficient data to support the idea that natural forces are responsible, therefore the skeptical argument remains purely speculative in my opinion. Evidence from the Cerutti Mastodon Site in San Diego suggests man was present in North America as early as 130,000 BP. If this is truly the case, the current archaeological record is certainly lacking as a means of supporting this theory. Unfortunately, with at least 42 archaeological sites providing evidence of Pre-Clovis occupation in North America, remnants of the Clovis first model can still be found in the craws of many archaeologists. A comparison between artifacts collected from these Pre-Clovis sites with those documented by Charles C. Abbott in the late 19th and an early 20th century reveals some amazing correlations. Prior to the 1930’s discovery near Clovis New Mexico by a paleontologist, it was believed that man’s earliest presence in North America was approximately 10,000 BP as theorized by Ales Hrdlicka, whom many of us consider as a blight to the history of North American archaeology.

It is what I refer to as a redneck skillset which is responsible for my own recognition of some of the ancient stone tools that I study. Experimental archaeology with lithic reproductions provides support for my hypotheses regarding usage as derived from my knowledge and experience of wilderness living and survival techniques. As a flint knapper and stone chipper, I have studied lithic technology in great depth. Too often lithic technologies are associated with time periods and human evolution with little regard to geological and geographical elements that can also dictate predominant lithic technologies. What is often referred to as flint in North America is typically anything but actual flint, which occurs as nodes inside of chalk formations that were once covered by oceans. Many lithic sources in North America such as chert were altered by heat-treating with fire to produce the desired results comparable to that of natural microcrystalline structures. Before the science of early man developed the techniques of pressure flaking and heat-treating there were only native stone and crude lithic technologies available. I believe that a better understanding of our ancient past can be achieved through a much wider peripheral view of the relationship between early man and the resources that were implemented establishing a viable existence. Ascension of the food chain in a vastly formidable and competitive environment such as Paleolithic North America cannot be overlooked as one of mankind’s greatest accomplishments, highlighting stellar ingenuity and an unstoppable will.

It is what I refer to as a redneck skillset which is responsible for my own recognition of some of the ancient stone tools that I study. Experimental archaeology with lithic reproductions provides support for my hypotheses regarding usage as derived from my knowledge and experience of wilderness living and survival techniques. As a flint knapper and stone chipper, I have studied lithic technology in great depth. Too often lithic technologies are associated with time periods and human evolution with little regard to geological and geographical elements that can also dictate predominant lithic technologies. What is often referred to as flint in North America is typically anything but actual flint, which occurs as nodes inside of chalk formations that were once covered by oceans. Many lithic sources in North America such as chert were altered by heat-treating with fire to produce the desired results comparable to that of natural microcrystalline structures. Before the science of early man developed the techniques of pressure flaking and heat-treating there were only native stone and crude lithic technologies available. I believe that a better understanding of our ancient past can be achieved through a much wider peripheral view of the relationship between early man and the resources that were implemented establishing a viable existence. Ascension of the food chain in a vastly formidable and competitive environment such as Paleolithic North America cannot be overlooked as one of mankind’s greatest accomplishments, highlighting stellar ingenuity and an unstoppable will.